Breaking challah, dipping apples in honey, and sipping Kosher wine – pull up a chair as Maya Glantz sees the light in her family’s Friday night dinner.

“A short summary of every Jewish holiday: They tried to kill us. We won. Let’s eat.”

The joke is old and has been repeated by too many ‘cool’ rabbis and Bar Mitzvah boys to make anyone laugh, but it does speak to one of the core aspects of Jewish culture – food.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a Jewish celebration that doesn’t revolve around food. Even on Yom Kippur, the day of atonement when tradition states you must fast for twenty-five hours, whispers of honey cake and challah reverberate around the synagogue. Growling stomachs are masked by the rhythmic bleats of the festival’s ram-horn instrument, the Shofar, being blown. “Where are you breaking it?” and “What are you breaking it with?” are the day’s major questions, followed shortly by “How much longer have we got left?”

I haven’t fasted for the past five years, not since I dramatically fainted mid-service, collapsing into the arms of my unsuspecting neighbour. I had only lasted until midday and was promptly rushed to the children’s playroom, where a carton of apple juice was shoved into my hands. Proving, single-handedly, that this fasting business isn’t made for us Jews. No, we’re much better suited to eating.

Now, instead of spending the day feeling dizzy in Shul, I join my mother in the kitchen, where we prepare for hours, creating a feast that our more diligent guests will be dreaming about while they atone for their sins. Glimmering slithers of oily smoked salmon are carefully arranged on a platter, ready to be strewn atop a bagel. Cakes spiced with cinnamon and studded with apples are slathered with a maple cream cheese icing, begging to be licked off with the swipe of a finger. Salads are bejewelled with pomegranate seeds, and greens are tossed with tahini. Wedges of apple are dunked into an amber pool of honey – offering wishes for a sweet new year. And even after all that, you’ll still have space for a slice of honey cake.

“This fasting business isn’t made for us Jews. No, we’re much better suited to eating”

The meal itself will vary from home to home, each family carrying their own traditions. In American Ashkenazi homes, brisket occupies a crucial place on the Yom Kippur table; for Jews hailing from Morocco, the tomato-based soup, Harira, is likely to make an appearance. There’s no one way to be a Jew – traditions formed by generations of displacement and relocation make for complex cultural intricacies. It often feels as though the string tying us all together is the importance we place on our food.

For many Jews, it’s at the end of the week – gathered round with your family for Shabbat dinner – that you feel the most connected to your religion. It could be seen as the Jewish equivalent of Sunday mass. But instead of a single wafer and a sip of wine, we have a three-course meal.

Even the prayer portion of the evening is a culinary delight – sinking your teeth into the warm, pillow-y challah bread and washing it down with a sip of the sickly-sweet kosher wine.

In our adolescence, my sisters and I resented this tradition at times, bitter that our friends were out chugging WKD while we sat at the kids’ table with our cousins. With time, I’ve come to appreciate these moments spent with my family.

While this ritual has been a weekly staple in my upbringing, it was not the same for my mother. “I can count on one hand the number of times we ate in a dining room growing up.” she tells me. Despite attending a religious school, and living within the Jewish suburbs of north London, my mother’s Shabbat dinners were usually taken on her lap, while sat in front of the TV.

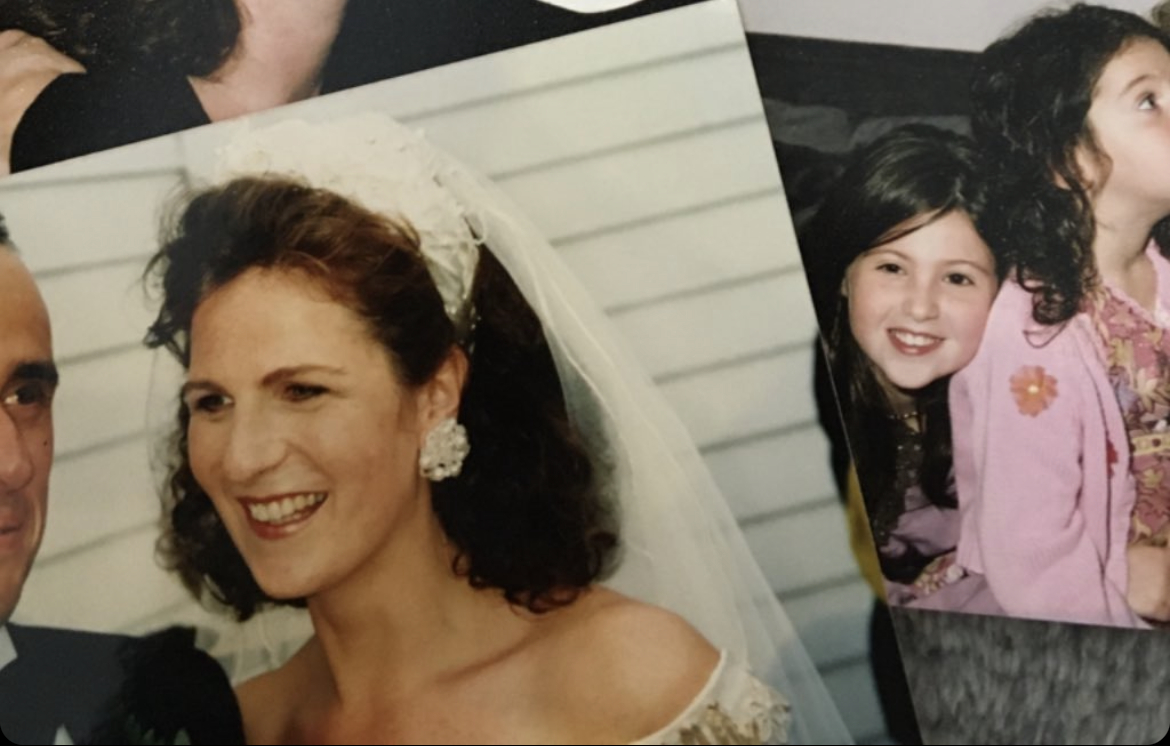

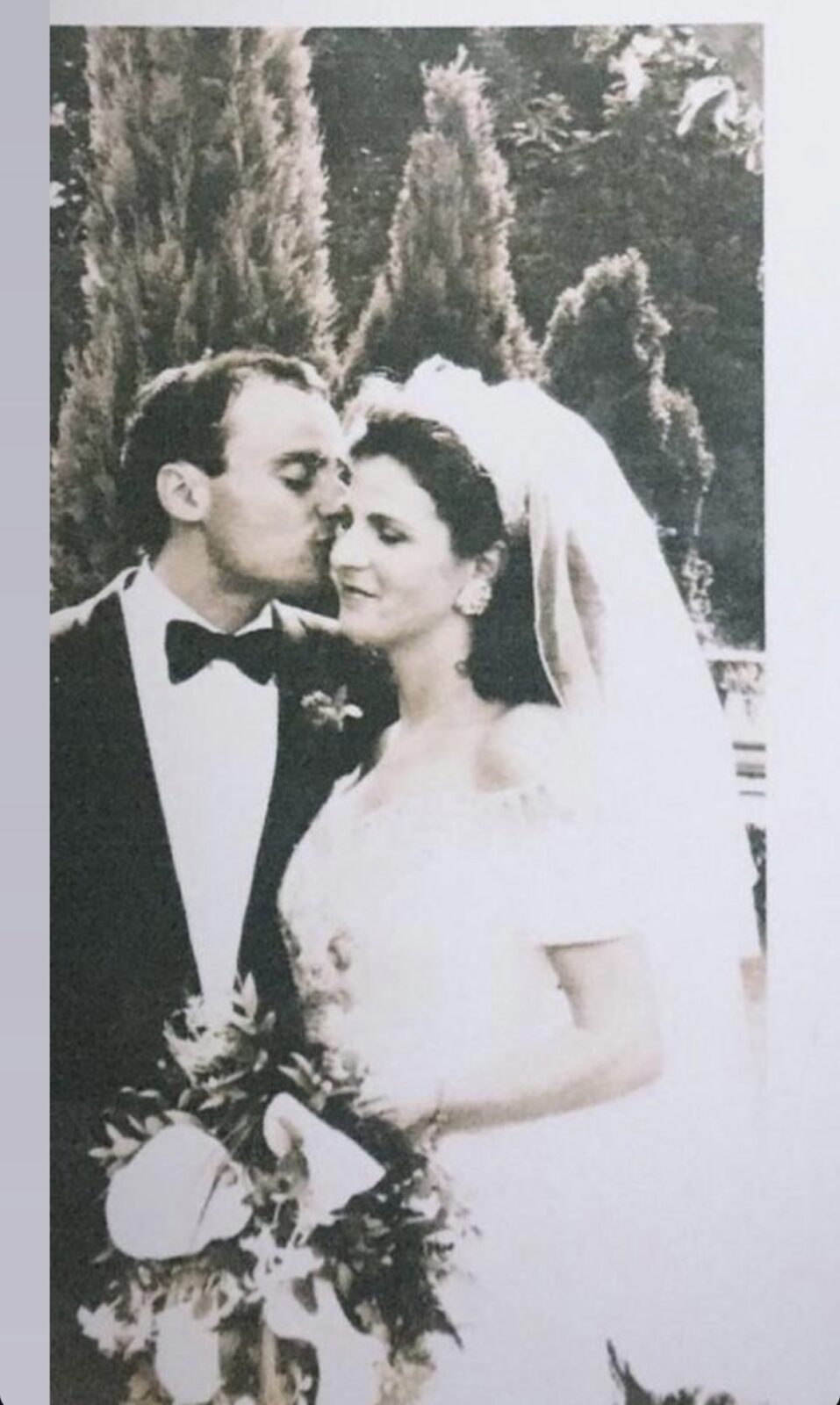

It was only by visiting her friends’ houses and observing their family dynamics that she saw the kind of community she wanted to create in her adult life. When she married my father, she discovered her love, and natural affinity, for hosting. And more importantly, for feeding.

For her, to host was a luxury, a celebration of the life she had always wanted. She became known for her spreads – chicken soup more rich and golden than anyone else’s, her meringues shatteringly crisp and airy, and there was always something new at the table, a recipe she hadn’t yet tried before. Her hosting style was informal and welcoming, if at times slightly frantic; ever-ready to set an extra seat at the table for any Shabbat stragglers. Our house was a hub for socialisation: she’d frequently joke about replacing our entrance with a revolving door. Though, despite these complaints, I have a sneaking suspicion she secretly delighted in the constant flow of guests. The never-ending stream of people, with stomachs to fill and problems to solve. Once the time came to go home, you’d be sure to leave full – of both food and advice, solicited or not.

After my father passed away, hosting became a less appealing prospect for my mum. Having to think of a meal to feed her three daughters was exhausting enough, the idea of cooking for a crowd was out of the question. “It felt weird,” she reminisces: “Feeding is such a big part of mothering and being Jewish. But I just couldn’t do it.” I feel guilty when I think back to these times, when my sisters and I would roll our eyes at dinner time, muttering “schnitzel again?” under our breath.

Over time though, she rediscovered the joy she once found in hosting. My sisters and I matured, and the responsibility was shared, removing some of the pressure that weighed so heavily on her. It became a source of bonding for us. We’d lie in bed flipping through cookbooks with one another, dog-earing the recipes we wanted to replicate for our next Friday night dinner. On the television, we took hosting tips from our culinary idols: Nigella Lawson and Ina Garten. She slowly became more open to accepting the help she was offered, allowing her guests to provide part of the meal – though she’d still rarely accept anything more labour intensive than a fruit salad.

Watching her map out, plan, prepare, and execute elaborate feasts, week after week, has provided me with a blueprint for how to raise a family. Her dedication to the weekly ritual has provided our family with a tangible way to connect not only to one another, but to our religion.

Religious institutions can be intimidating – it’s rare that I’ll step through the arched doors of my synagogue more than three times a year. But on a Friday evening, as we stumble over the correct order to say the blessings, I feel lucky to be Jewish.