From parsley sauce to pie and mash, East End cuisine is Britain’s home-grown fast food. Feast your mince pies as Katie Baxter takes a trip down memory lane.

My childhood was centred around Grandad Charlie’s leather armchair. I, along with his 14 other grandkids, would spend Christmases, birthdays, royal jubilees, and race days gathered on the rug in Nanny and Grandad’s Camden living home – a sea of children flocking around Grandad Charlie holding court and observing his kingdom. He was an ever-dependable presence, shrouded in cigar smoke, picking through pistachios and sipping a glass of merlot.

If there’s one thing Grandad Charlie loved more than his armchair (and Nanny Carol… and his family… and his cigars… and his gambling) it was pie and mash. Most UK families are no strangers to a takeaway – the most popular takeaway cuisine in the country is Chinese, followed by Indian, and fish and chips. However, increasingly few are likely to head down to their local pie and mash shop for ‘double double’ (two pies and two mash) and Tizer, or jellied eels and mash doused in lashings of ‘liquor’ (not the hard stuff, but rather the watery parsley sauce). I grew up fed by this little-known culinary tradition of Cockney cuisine.

This unassuming (and perhaps to some, unappetising) dish is one of London’s first home-grown fast-foods. It came into its own during the Victorian era when pie and mash shops started popping up all over London. The dish’s epicentre was mostly in the East End, where much of the Cockney community resided at the time. Eels were cheap and easy to come by – plucked straight from the river Thames and encased by equally cheap stodgy pastry which protected the meat within, making for an affordable favourite for working-class coalmen, tradesmen, and locals.

My auntie, Mandy Chapman, recalls eating pie and mash as a little girl growing up in the 60s and 70s. It was one of the few foods she agreed to eat as a fussy child, but it had to be served with particular specifications. “It had to be swimming in liquor and smothered with lashings of vinegar – so much liquor that you would need a spoon to eat it,” she says. “The shops themselves were different then: if you ate in, you sat at big long tables with other people, and I remember watching all the old people eating their jellied eels and taking the bones out of their mouths and putting it back on their plates.”

“Every Cockney is a loyal advocate of their local pie and mash shop; they swear that theirs is superior to the rest“

Ordering pie and mash (and jellied eels for Nanny) was a family ritual on most Saturdays throughout my aunty’s childhood, particularly on sporting occasions. The Grand National and the FA Cup Final would be catered for with pie and mash. “I remember my mum and dad coming home with a large cardboard box packed full of pies,” my aunty says. In the absence of takeaway boxes, Mandy would be sent to the shop with her brother with a large plastic bowl for the mash and a jug for the liquor.

My dad, Ian Baxter, and his brother, Andy Baxter, grew up eating pie and mash, too. But their most poignant memories of pie and mash come from the days they spent working together on market stalls across London in the 80s, throughout their teens and early twenties. Ian describes their youth as “Only Fools and Horses in real life”. After a long day on the market stalls, my dad and uncle would return to their old van and make their way to Castle’s Pie & Mash on Royal College Street – they were, and continue to be, loyal devotees of this particular shop.

Andy fondly recalls the woman who would always serve him at Castle’s, called Joan. “She must’ve been working there for over 50 years. She started working there just after the Second World War. I remember her spooning the pie and mash into the bowls with a flat spatula – she had been doing it so long that she had become a master at it.”

Every Cockney is a loyal advocate of their local pie and mash shop; they swear that theirs is superior to the rest. While I had grown up eating at Castle’s with my family, I decided to venture across the river to M.Manze in Tower Bridge, which is the oldest surviving pie and mash shop in London, founded in 1892.

Entering M.Manze feels like stepping back in time – the original wood benches and green tile work adorn the interior. Photos of celebrity visitors, including Rio Ferdinand and Rob Beckett, are proudly positioned on shelves above the countertop. I order a ‘double double’ (as is the done thing), and sit myself down in the same spot Victoria Beckham, East End royalty, allegedly once sat. Around me, older locals in their flat caps order their usual, clearly familiar with the warm and friendly women serving them – everyone is “darling” and “lovely” here.

M.Manze is one of only a handful of surviving pie and mash shops in London. It used to be a thriving chain, 14 shops strong, across the city – now only three remain, with the original shop in Deptford set to close its doors next year. Many of the shops my dad and his family reminisce about are long gone: F.Cooke in the now trendy and gentrified Broadway Market, or Balmford’s in Bermondsey.

Times are changing, and the slow decline of pie and mash shops in London is inevitable. The clientele is dwindling, as Cockney residents and shop owners slowly up-sticks out of the city due to the rising cost of living and gentrification edging them out of what was once pie and mash shops’ turf. But their sturdy legacy remains, and traces of pie and mash shops continue to linger, sometimes in unexpected places.

Grime songs – also birthed in the east end – are laced with references to Cockney fare, like in the opening lines of Kano’s This is England. Pie, mash and jellied eels are embedded in the places that birthed them. While pie and mash shops may continue to close across the capital, they proliferate elsewhere, as the Cockney community moves outwards to Kent and Essex.

For me, the significance of pie and mash extends far beyond the physical stores that remain. A takeaway from Castle’s Pie & Mash was the last meal that both my nanny and grandad asked for before they passed away. Their children attentively brought their usual orders to the hospital for them, just like they had done growing up. As always, Nanny requested jellied eels with her pie and mash – she was the only one in my family who ever did.

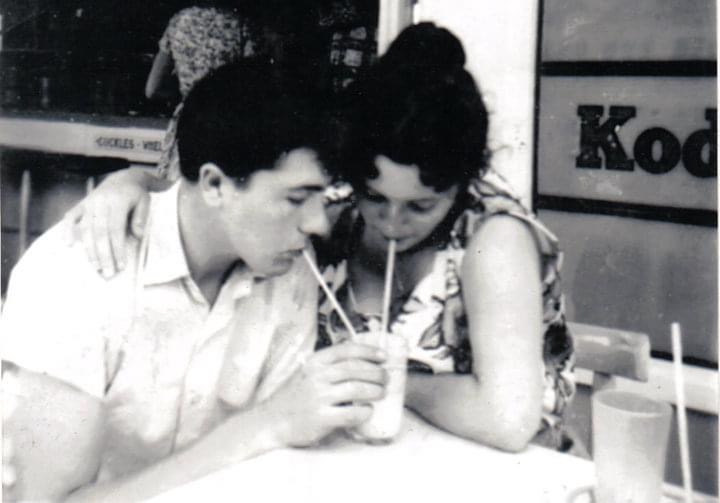

A lot changed throughout my nanny and grandad’s lives. Their time together started in a basement flat in Holloway, north London, in the early 60s, when at 16 years old, they had their first child – my dad. Fast-forward to the late 80s, when they had their sixth child, my aunty Annie, at the age of 44 in the comfort of their beautiful Camden home, brimming with children, food, love, and warmth. Through it all, pie and mash remained constant – it was something they returned to again and again. It was so deeply rooted in their lives that it brought them immense comfort. Whenever I eat it today, I think of them – their tenacity, the sacrifices they made for their family, and the unwavering love they had for one another.