It tastes like chicken and looks like crispy duck. In Peru, one man’s pet is another man’s platter, says Millie Jackson.

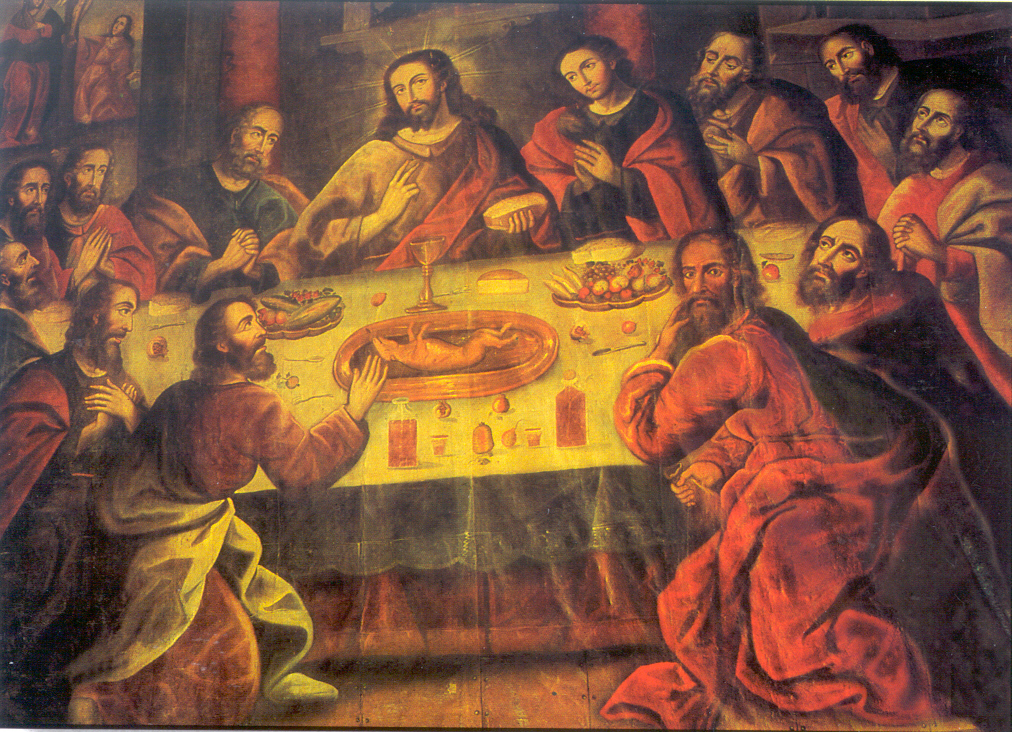

Under the arching ceiling of Cusco Cathedral, Peru, is a familiar sight for a church – a painting of The Last Supper. Disciples robed in deep red, green, and brown sit with their hands clasped in prayer and thanks, faces upturned towards Jesus. In one hand he holds a loaf of bread; before him is a goblet representing the blood and body of Christ.

What’s perhaps less familiar is that in front of Jesus and the disciples is a roasted guinea pig on a golden platter, legs up. Most eyes are clearly on Jesus, but there are one or two disciples staring at the glistening delicacy, their stomachs surely rumbling.

“Along main roads in towns, there can often be found enormous painted guinea pig statues advertising a nearby restaurant. Often the guinea pigs are wearing chef hats.”

While Jesus is haloed and centre stage, it is the table that draws the eye. The tablecloth is painted noticeably lighter than its surroundings. Holy light seems to grace the table, too, as it is filled with offerings from the land. Besides the guinea pig, there is corn, potatoes, rocoto relleno (stuffed peppers), and chicha, a drink made from fermented corn.

The artist, Marcos Zapata, belonged to the Cusco School, a group of native Peruvian and European artists that formed when the Spanish first took over the city from the Incas. Many paintings created by artists who refused to convert to Catholicism are unsigned, and displays of Peruvian culture were not often allowed.

Fast forward 271 years and the tradition of eating guinea pig in Peru is still very much alive. Along main roads in towns, there can often be found enormous painted guinea pig statues advertising a nearby restaurant. Often the guinea pigs are wearing chef hats, the traditional clothes of the Inca, or pointing inside where their mortal relatives can be found roasting over a barbeque.

Guinea pigs, or cuy as they’re called in Peru (supposedly because of the sound they make), are eaten on special occasions, like birthdays or anniversaries. High in protein, but lower in fat, the cuy is said to taste like chicken and look like crispy duck when prepared.

Sara from the Peruvian restaurant Quinoa Arepa says: “It’s a very delicate animal. The skin is very thin and you’ve got to be very careful when you peel it because of the hair. Nowadays in Lima, you don’t eat it; only in rural areas.”

There are pens of guinea pigs outside some houses and restaurants, while others live under the floor of the wattle and daub houses found in rural areas, warmed by the oven that heats the whole house. Traditionally, guinea pig is served with one of the 4,000 varieties of potato that grow in the Andes, corn on the cob (much larger and a more pale yellow than the British version), and salsa huacatay (a salsa verde equivalent made with mint).

“The guinea pig is cooked with the teeth, head, and ears still intact.”

Cuy al horno (baked guinea pig) is popular in Cusco. After the guinea pig is gutted and de-haired, the meat is marinated in garlic, aji amarillo (yellow chilli), cumin, oil, chicha de jora (fermented maize drink), huacatay (black mint), black pepper, and salt for an hour before being placed in the oven with potatoes.

Arequipa, a Peruvian city that sits in the shadow of no less than nine volcanoes, favours the deep-fried version of this dish, cuy chactado. Half a kilogram of flour is recommended, with spices such as cumin to coat the guinea pig, which is then fried in a vat of vegetable oil.

Variations include cuy al palo (guinea pig on a stick), and pepian de cuy (a guinea pig and corn stew).

Traditionally, one guinea pig will be shared by many people alongside a host of smaller dishes featuring peppers, potatoes, and sometimes tortillas.

Sounding tempting? Be warned – the guinea pig is cooked with the teeth, head, and ears still intact, so it’s not a dish for the squeamish.