Millie Jackson explores the effects war has on mealtimes across Nazi Germany, Ukraine and Gaza.

My grandmother was born in 1937, in a little village in south Germany, two years before the start of the Second World War. She was nine when the war ended, but the after-effects were everywhere, especially in food. She was about 12 the first time she saw imported fruit: “I thought oranges were beautiful and bananas looked funny.”

She tells me: “Food was very plain, but I was so young I didn’t know anything different. I hadn’t lived before the war. But we always had a dinner, no matter how simple. It got very difficult but, well, we survived.”

From 1940 to 1941, senior figures in the Nazi party were responsible for the creation of the Hunger Plan, whereby German citizens and soldiers were given priority access to food supplies over people in German-occupied Soviet territories.

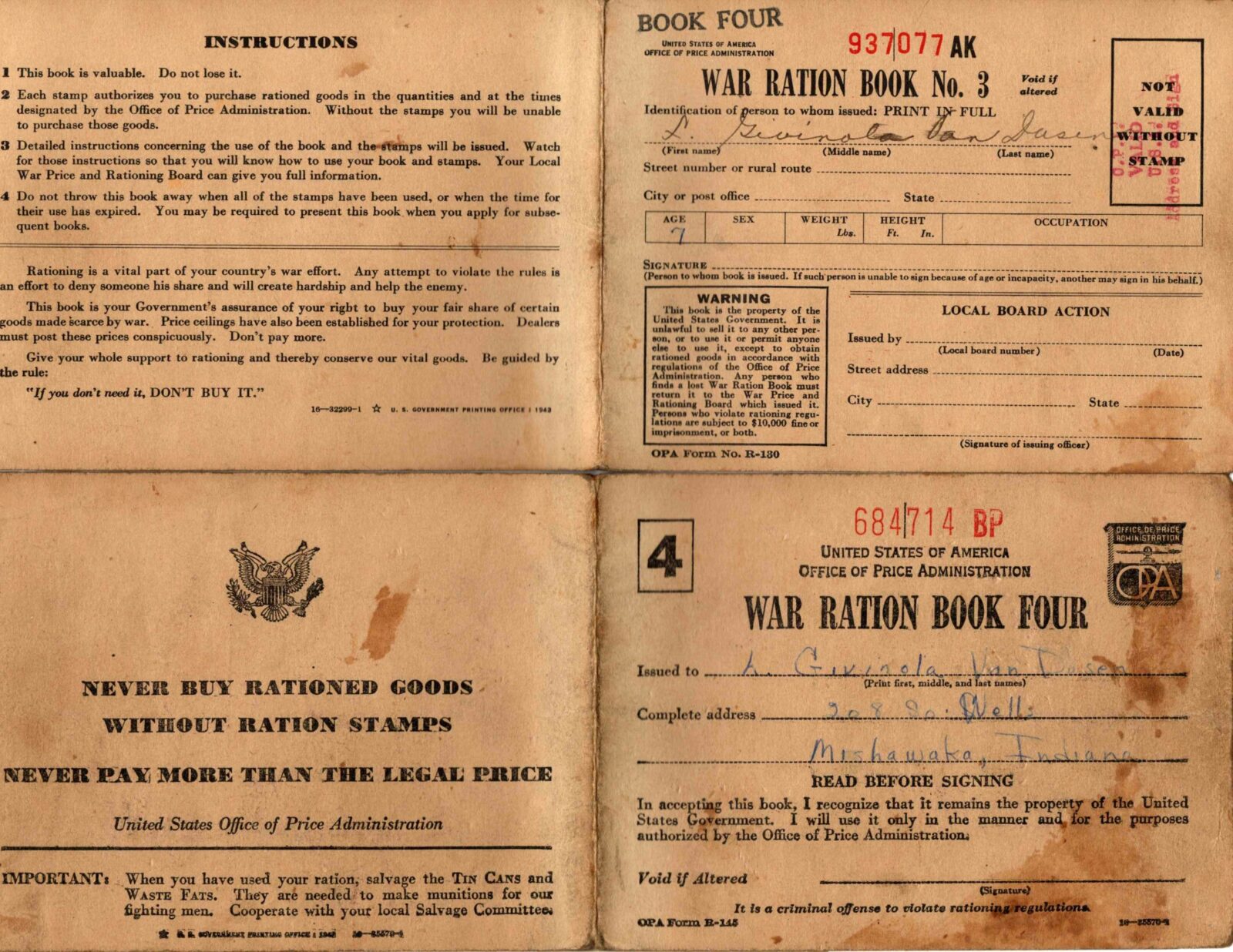

Nonetheless, rationing started in Germany in August 1939 and did not stop until 1954. My grandmother remembers the effect of the war on herself and local families.

“I remember going hungry only as a child would, if I was coming home from school. If I was hungry, I’d get another slice of bread. I played with one of the girls who was in my class and their siblings, and they were always hungry – they only lived on what they got from their rations. There was no more bread available. They only had the ration book supply.”

Katrya Seldonenko is a Ukrainian baker who was displaced from the now-occupied Kherson region in the south of Ukraine. She says: “My ancestors, like the majority of Ukrainians, experienced great traumas connected with food: the Soviet occupation, Holodomor – genocide of the Ukrainian nation by man-made famine – the Stalinist regime and the World War II. All these factors affected our relationship with food. It means a very thrifty attitude to food and the sacredness of bread.”

“I started to care about every piece of bread or food on my table. I have no right to waste it, especially now”

Katya Seldonenko

Recent reports from the conflict in Gaza describe people eating donkey meat and grinding down animal food to make flour as aid deliveries are allowed through in too small numbers.

Seldonenko relates a similar tale of scarcity from Ukraine: “When the Russian forces occupied some regions in Ukraine in 2022, people faced the absence of bread, yeast, flour and shortage of food supply there. I was one of those who needed to survive under those horrible circumstances. It was absolutely devastating to me. I spent 43 days under the Russian occupation, and when I managed to flee to Lviv, I started to care about every piece of bread or food on my table. I have no right to waste it, especially now.”

The reminders of war still shape my grandmother’s life today – she’ll clear all the white out of an eggshell with her finger, go scrumping around the apple orchards of Berkshire to collect apples abandoned in grassy gardens and won’t waste a crumb. Leftovers are tomorrow’s meal, and out of date is only out of date when it’s inedible.

She recalls: “Once a year we reared a pig, and after Christmas the butcher came and killed it in our yard. In our wash house, which had been scrubbed clean, he cut it up and boiled it in a big kettle.

“It was a whole ritual, and everything was used, even the tail of the pig. One of my uncles liked it and I remember every year having to take it to him with broth. The butcher took some of the meat with him and smoked it to make rauchfleisch and salami.

“Some of the meat was preserved and we put some in tins if we could get hold of them, but I think that was later. We wouldn’t have been able to get tins during the war.”

Wafa Shami is the chef and writer behind the food blog Palestine in a Dish. She recalls the importance of community and family meals on special occasions, and Sundays, when her late father was off work and the children home from school. Her mother would cook elaborate meals made up of dishes such as warak dawali (stuffed grape leaves), chicken fatteh (layers of bread soaked in chicken broth topped with rice, chicken, and toasted almonds or pine nuts), or musakhan (roast chicken placed on taboon bread covered with caramelised onions spiced with sumac).

Shami lived in Palestine under occupation until she was 29. “Palestinians are self-sufficient,” she says. “We always had enough in our pantry to survive days, or even weeks.”

“People live off of these olive groves – Palestinians purchase olive oil in big buckets – but they also take care of these trees as if they were children”

Wafa Shami

Traditional recipes passed down through generations may be lost in a conflict that has displaced and killed so many. Shami reflects: “We feel our land was stolen and that makes us even more connected to it; in our culture, a piece of land is very important.”

Land and self-sufficiency was what kept my grandmother from going hungry 70 years ago. Growing up on a small farm meant it was possible to live from it. “We had our own flour, milk, potatoes and eggs, and I went out on Saturdays to buy meat, pasta, salt and sugar.”

The local families existed in a symbiotic relationship with each other. “People would help us on the farm in the busy season and in exchange they got a couple of pints of milk from the cow or six eggs. One family stocked us up with their linen, so once a week I brought them a litre of cow’s milk.”

In her children’s storybook, Olive Harvest in Palestine, Shami writes about a core part of Palestinian cuisine. She says: “People live off of these olive groves – Palestinians purchase olive oil in big buckets – but they also take care of these trees as if they were children. They really care.”

The olive groves of Palestine and the apple orchards of southern Germany in World War II may be separated by both time and space, but the principles of harvesting food and living from the land remain.

“Everything was harvested, nothing was wasted. Every morning, I had to go up to the orchard where the pear tree was and pick up all the pears. They got made into a spirit – schnapps. We had so many apples in autumn – you could eat as much as you wanted, but I wasn’t allowed to throw any away – right up to the core. I was told if you waste food, it’s a sin, which it is, really,” my grandmother remembers.

Apples were boxed and stored, and any that couldn’t be used were taken to the local press to make cider. There was an announcement in the paper so locals knew when to go, and people would load baskets of apples onto wagons in the evening and make a few marks.

This way of living feels so removed from the way we are with land and food today, especially in the UK. While there can be no positive outcome from war, it serves to remind us of what we have and to be grateful for the land that provides.

Finally, my grandmother says: “If you go into Germany now in the orchards, there are apples lying on the floor. They don’t want them anymore.”