Yasmin Vince investigates how the UK’s flaky, sausage-covered snack may find its roots 4,ooo miles away, in Uttar Pradesh.

If you go down to the woods today, you’re sure of a big surprise. It’s not the teddy bears having a picnic that’ll astonish you, but what they’ve packed. In the centre of the basket, there’s what looks like a scotch egg. Except it’s missing the breadcrumbs and smells like tandoori chicken. The staple of English picnic cuisine has been swapped out for its Indian counterpart, the nargisi kofta.

Developed in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, during the Moghul Empire, it’s possible the nargisi kofta is the predecessor of the scotch egg. One theory behind the English snack’s development is that it was introduced to Britain by those returning from India in the 1700s. “Since so little else has moved from Britain to India, it’s unlikely the scotch egg came first,” says Monsiha Bharadwaj, a chef and Indian cuisine historian now based in London.

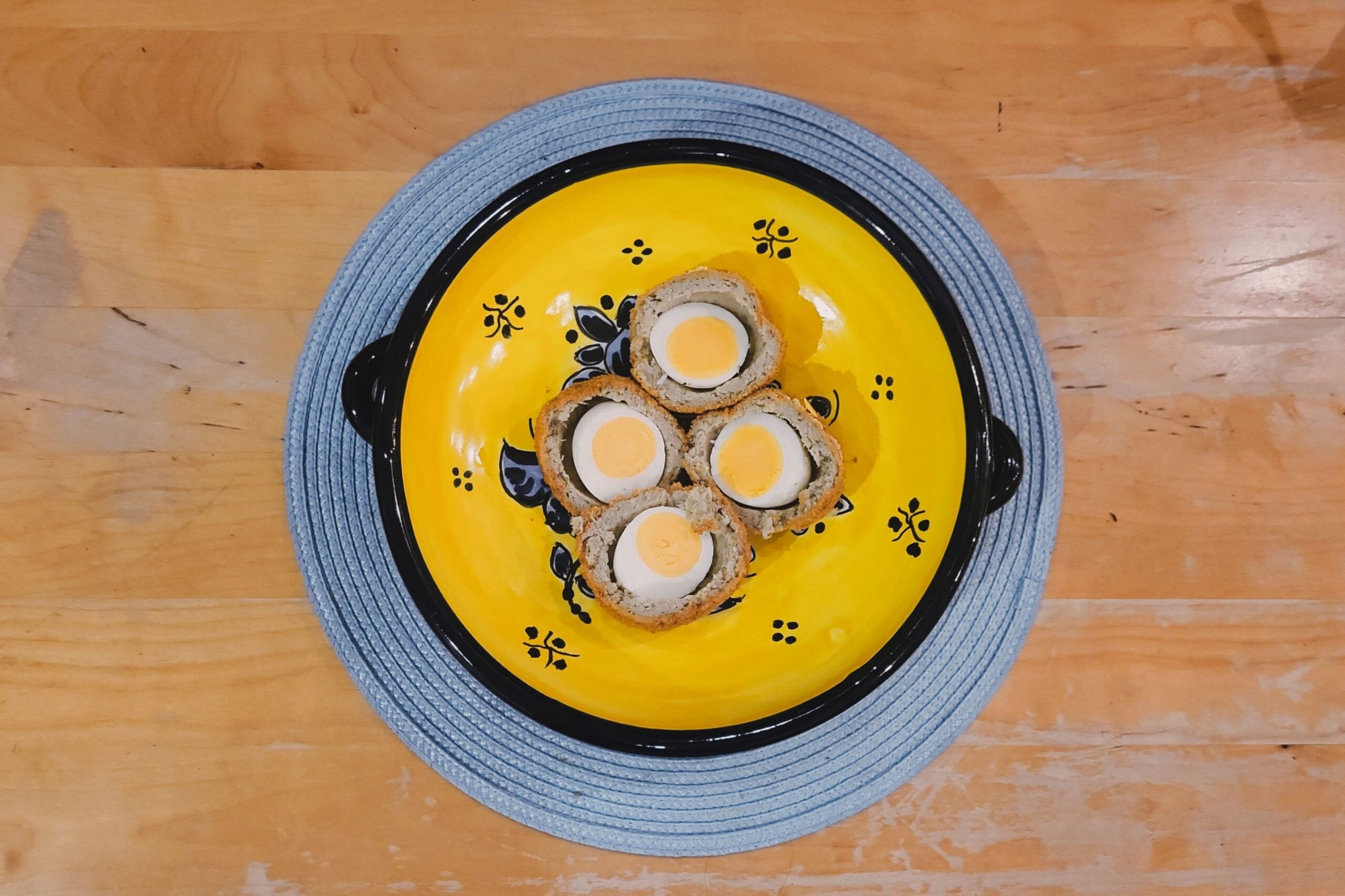

The similarities between the scotch egg and nargisi kofta are striking. The basics are the same: both are boiled eggs, surrounded by meat, and then fried. But the Indian version uses minced goat or lamb meat instead of pork sausage, which the Scotch egg opts for. According to Bharadwaj, the fattiness of goat and lamb means it holds together well and is more flavourful. The two meats are staples of Indian cuisine as neither is prohibited by the variety of religions in India, like Hinduism, Islam, and Sikhism.

The nargisi kofta is also packed with spices, such as garam masala. This gives the dish a more complex flavour palate than the scotch egg. The differences do not stop with the ingredients. While those trying to elevate the English version often leave the yolk of the egg runny, this never happens with the kofta. “Because of the heat and risk of food poisoning, you never get partially cooked animal produce in Indian cuisine,” says Bharadwaj.

The combination of drier meat and a hard-boiled egg in the Indian snack means it risks being crumbly. Hari Kamuluddin, a UK-based chef who tries to make Indian cooking accessible, offsets this by cooking the kofta in a curry or serving with something else. “I love to serve these with a zingy mango kachumber or put them into masala,” she says.

Both the nargisi kofta and scotch egg may have started as snacks for the wealthy. The nargisi kofta was developed for the ruling classes during the Mughal era. In India, it remains an expensive, elaborate dish, saved for special occasions – its luxurious flavour signals its upper-class origins.

Meanwhile, Fortnum & Mason claim (to some dispute) that they invented the scotch egg as a snack for rich travellers to enjoy in their carriages. Now, it’s enjoyed widely, with little information on at what point it might have crossed the class divide. Some suggest it was, in fact, a relative of the Cornish pasty, consumed for lunch by working men.

“Since so little else has moved from Britain to India, it’s unlikely the scotch egg came first”

Monsiha Bharadwaj

Despite the widespread availability of the scotch egg, the nargisi kofta is hard to come by in the UK. It remains a local delicacy, and Indian restaurants in the UK rarely offer it. Chef Bharadwaj remembers making it in Mumbai when she was learning to cook: “In India, it’s a luxurious dish. It was more flavourful, more nuanced than a scotch egg.”

So, pack up the basket and head down to the woods. Today’s the day the teddy bears have their picnic and whether they stick with the English classic or the Indian original, they are eating well.